World first: trials begin to seed the threatened Great Barrier Reef with thousands of healthy baby corals

In what’s believed to be the world’s largest coral restoration research trial, the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) and collaborators are releasing 100,000 new baby corals on the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) to develop new tools to help coral reefs recover after disturbances such as coral bleaching.

The healthy baby corals, which are about 1mm in diameter, were reared in large aquaculture tanks at AIMS’ National Sea Simulator (SeaSim).

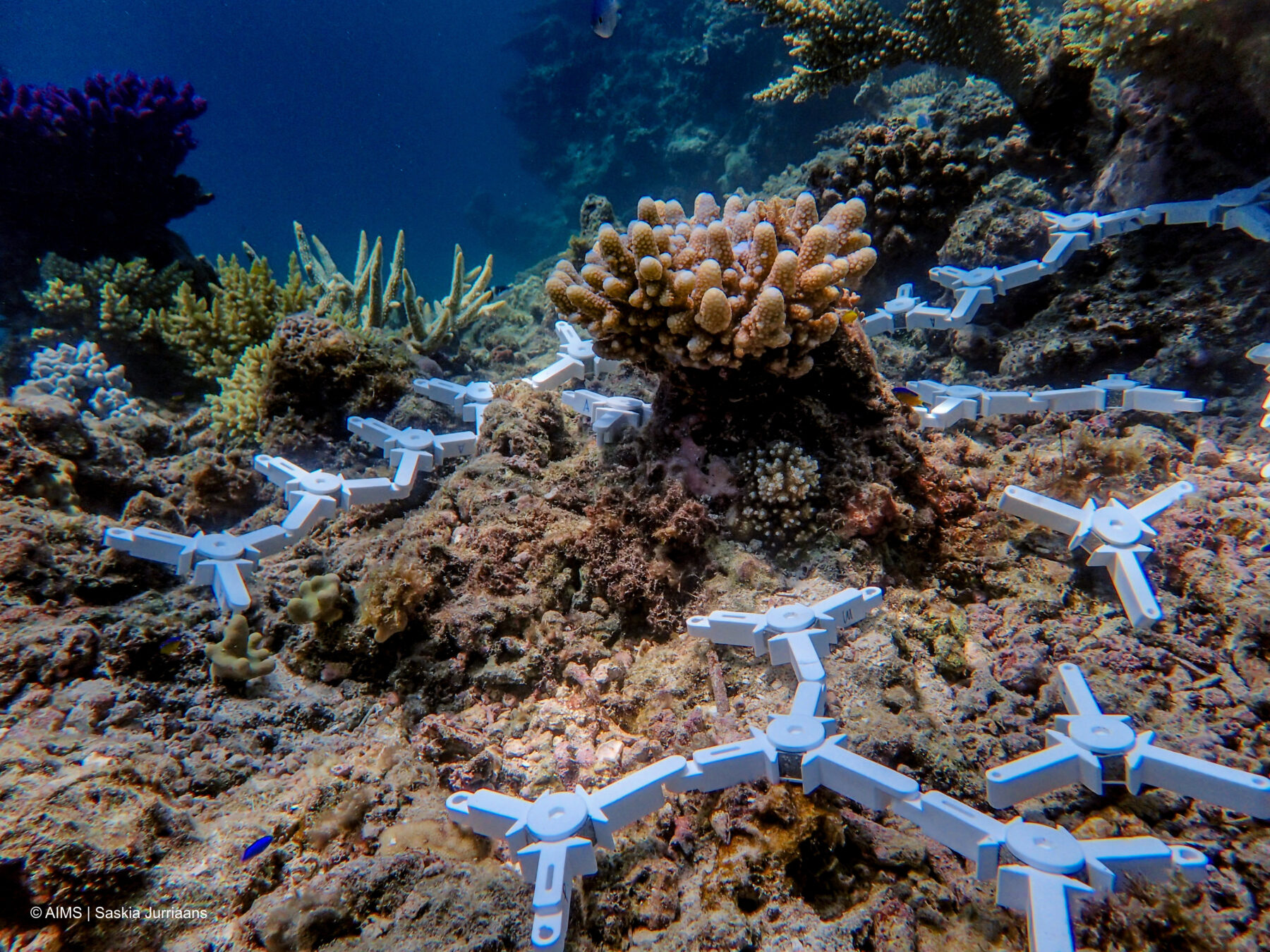

The corals were settled onto small concrete tiles and then attached to 10,000 ceramic “coral seeding” devices, which are being deployed in the central region of the Great Barrier Reef during two field trips.

Reef help, but no silver bullet

Dr Line Bay, AIMS research program director and sub-program leader of the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program (RRAP), stressed that coral seeding is yet another tool in reef conservation but is not a “silver bullet” solution.

“The intent is not to replace every coral on our reefs,” she said. “That’s just madness – there’s no way that could be done.

“What we’re doing at the moment is research and development for restoration and adaptation tools, to be available and ready for when managers and decision-makers think it is the time to implement them.

“But it should only be done so with strong emission reductions and the conventional management that’s already working very well.”

In 2021, RRAP successfully trialled 300 coral seeding devices in the Keppel Islands, off the Central Queensland coast, followed by 2,000 devices in 2022.

“Over the last four years, we’ve increased our knowledge and coral methods enormously, where we are now able to seed up to 10,000 of these devices onto the reef in a single season, or single spawning event,” Line explained.

“This is not the end for us; we’re aiming much higher and we’re looking at further enhancing these tools in the coming years to be able to deliver millions of corals.”

Massive goal

Delivering millions of corals onto a reef might sound like an ambitious goal, but it’s certainly feasible.

Each October to December, during the GBR’s annual mass coral spawning, millions of coral larvae are produced inside AIMS’ SeaSim aquaculture tanks.

This process is being fine-tuned by new technology such as the AutoSpawner, which can produce up to seven million larvae in a single night.

As well as increasing the number of coral larvae produced for the trials, it’s also made the fertilisation process less labour-intensive for scientists.

“[When] corals spawn they have buoyant gametes – bundles of egg and sperm – that float to the surface,” Line explained.

“The AutoSpawner skims these into a receiving tank, where the bundles break.

“Then we add some more water to make sure the sperm concentration is about right, within the range where we know we get optimal fertilisation.

“This system is pretty much automated, so in a single night, the [AutoSpawner] can produce millions of coral larvae, with really only one or two people managing that system.”

High mortality rate

After fertilisation, the coral larvae settle onto prepared surfaces and develop into young corals, or polyps.

Most, however, won’t survive to adulthood.

Line explained that corals have a huge reproductive output but enormous mortality in the first 1-2 years of life, due to predation, competition with algae, and other factors.

To improve a coral’s chance of survival, RRAP scientists have engineered different types of seeding devices, tweaking designs for different marine environments, reefs and coral species.

The devices help the corals survive their first year and include defensive protrusions that protect corals from grazing fishes, and “slippery surfaces” that act like antifoulants to deter algal growth.

“There’s a whole range of different features we’ve trialled and tested over the past few years,” Line said.

“On average, we can increase the survival, at the device level, after one year to about 50 per cent.

“That is like a huge change over what might naturally occur on a reef, where much, much less than one per cent would often survive.”

Once the corals are deployed to the reef, their progress will be monitored every three months.

Spawning activities in SeaSim are conducted in collaboration with Taronga Conservation Society, The University of Queensland, Southern Cross University, James Cook University, Griffith University, and Queensland University of Technology. RRAP is funded by the partnership between the Australian Government’s Reef Trust and the Great Barrier Reef Foundation