The Golden Age of Magic

It’s Australia, circa 1900s, and you’re on the hunt for some entertainment.

There’s no streaming services, no television, ‘the talkies’ haven’t hit cinemas yet. In fact, there are no cinemas.

It’s time to put on your Sunday best and head to the theatre for a magic show.

It was the age of fabulous illusions, famed tricks and fantastic sleights of hand.

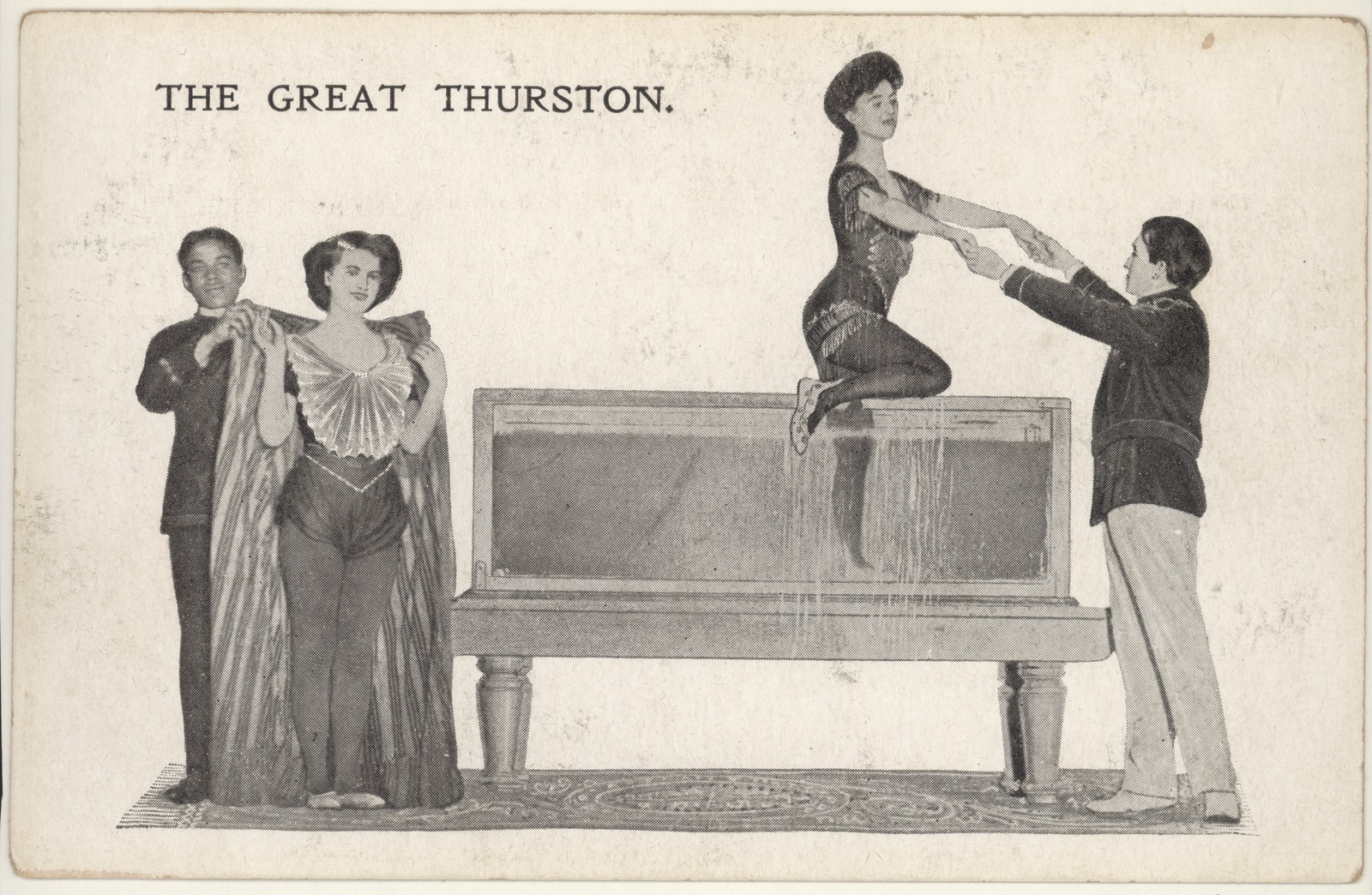

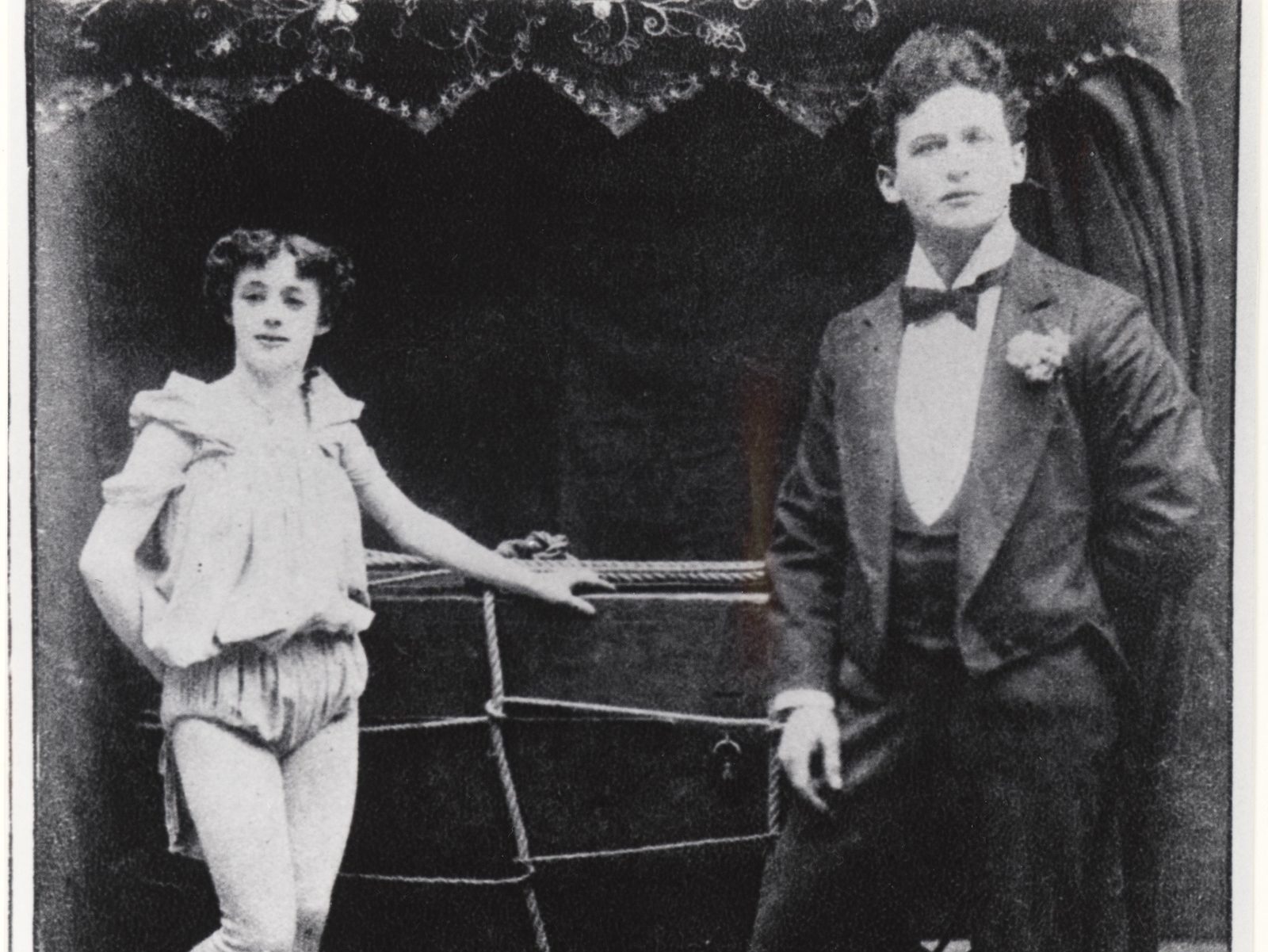

Magicians wore the finest of dinner suits, flanked by glamorous assistants. They saw women in half, swallowed swords, caught bullets in mid air, levitated, made things metamorphosise and escaped the seemingly inescapable.

It was, indeed, the Golden Age of Magic.

The general consensus among historians is that the Golden Age of Magic spanned the years 1880–1920.

But to understand this era, it’s worth looking at the events that came before it.

Magic’s early pioneers

Before being recognised as a legitimate art form, magic was the trade of sketchy conjurers – tricking people in the streets and working the carnival circuit.

Two magicians are credited with taking magic from low brow to high. They cleaned it up and created sensational spectacles, worthy of theatres and paying audiences.

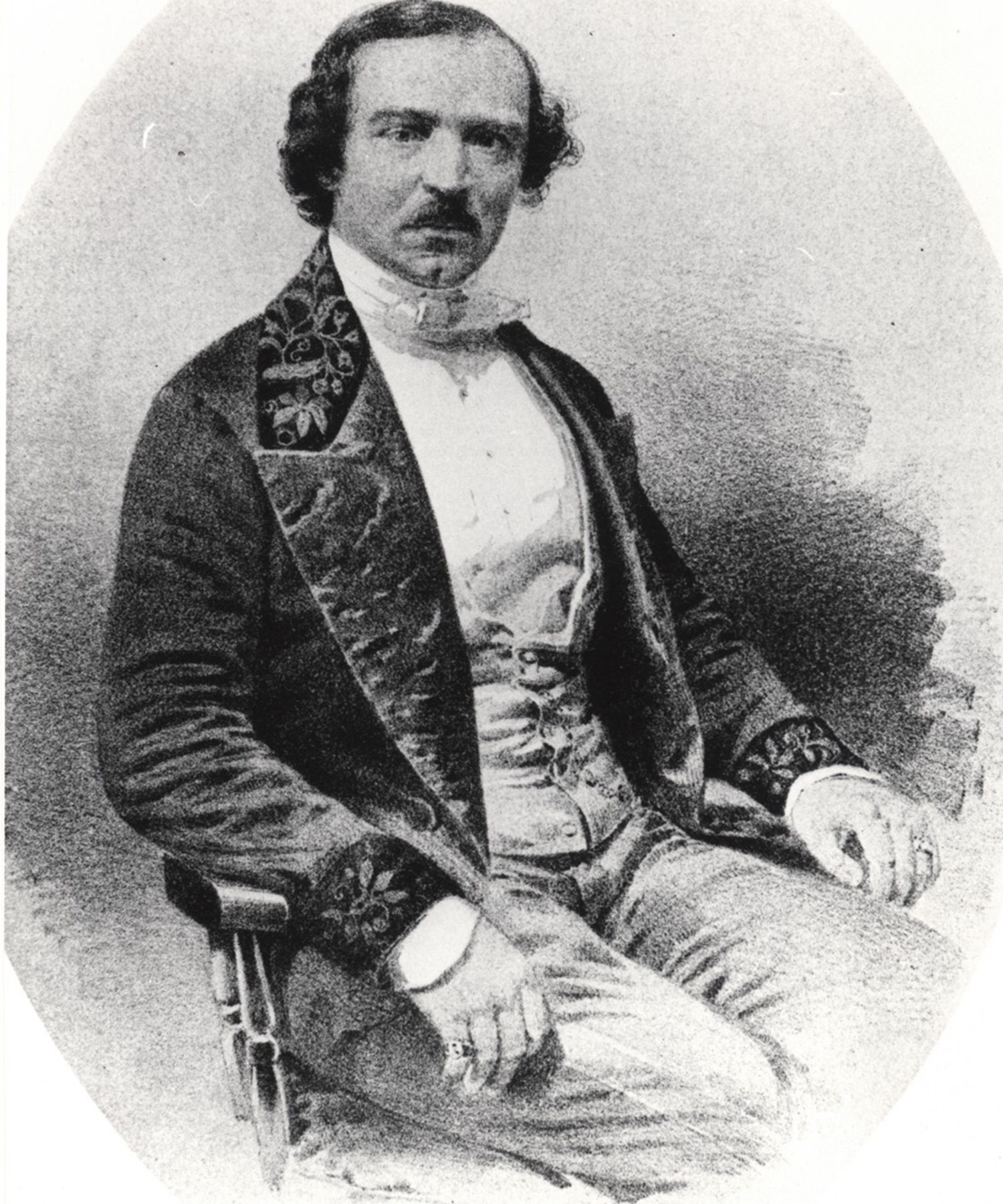

The first was a Frenchman, Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin. If this name sounds familiar it’s because famous American magician Harry Houdini later named himself in homage to his idol.

Robert-Houdin was the first magician to pull on a tailcoat tuxedo and appeal to the upper hierarchies of society.

“He was very suave and had a very beautiful saloon-style presentation,” says cultural historian Margot Riley, who recently curated an exhibition about the Golden Age of Magic at the State Library of NSW. “He was really operating to the upper echelons of French society.”

He was also a watchmaker by trade, the skills of which spread over into his phenomenal tricks. “He specialised in very sophisticated styles of illusions,” Margot says.

The second trailblazer was Scotsman John Henry Anderson, aka ‘The Great Wizard of the North’. Anderson was incredibly theatrical. An actor himself, he’d also acquired a string of theatres. He captivated audiences with his expert showmanship, and popularised the trick of pulling a rabbit out of a hat.

But perhaps Anderson’s biggest contribution to magic was his ability to spruik it.

“He was a businessman and a promoter, he really understood how to sell something,” says Margot. “Because, really magic doesn’t exist – it’s an idea. Many of the promotional techniques that we are now familiar with started with Anderson.”

The elaborate, verbose language that is now synonymous with magic also began with Anderson.

“It was all meant to bamboozle,” says Margot. “He was performing to working class people, people without a lot of education – for them to see him up there talking in this incredibly flamboyant kind of language was just as mesmerising as the magic.

“It also distracted people from what was actually going on. It was the patter, the language, the art of performing that was part of the trick.”

The Golden Age

With Robert-Houdin and Anderson paving the way, this new spectacular, sophisticated style of magic took off across the globe.

Soon, stage show magicians were performing their dazzling illusions and bamboozling tricks to sell-out crowds in theatres and music halls throughout Europe and America.

Acts like Harry Houdini, Howard Thurston, Carter the Great, Dante, Charles Bertram, Maskelyne, Devant, Harry Kellar, Herrmann the Great, Bernado, and many others, became household names.

This group of master magicians were among the highest paid and most famous entertainers of their time.

Meanwhile, Down Under, an appetite was growing for the kind of entertainment magic provided.

“Gold had been discovered so the population had exploded,” says Margot. “There were people with money to burn and they had leisure time.

“People were coming from the country into the city looking for entertainment and diversion – the more extravagant and exciting, the better.”

Magic also appealed to all demographics and social classes.

“It was family entertainment. It was a nice clean night out, and it was glamorous.”

You’d think it would have been difficult to sign these superstar showman up for tours all the way down here in Australia, but it turns out our geography worked in our favour.

“There was a global circuit,” explains Margot. “They’d come from America, from Europe, so travel to Australia was off-season. While it was winter in Europe they were able to travel to Australia in summer.

“And it was important for them to keep earning and keep performing. So they were keen.”

Soon, theatres were sold out across Australia, and new theatres were rapidly being built to accommodate (and entice) the travelling magicians.

“Audiences spanned from country folk who saw the shows in regional theatres, through to the highest echelons of society in the cities, who were just as much entertained.”

Mark Mayer, current president of the Australian Society of Musicians, says the performances had widespread popularity and catered to all demographics.

“Everybody was there,” says Mark. “In the front seats would be all the wealthy people, and then they’d have the ‘nickle and dime’ seats at the back for all others to be able to go.

“They were variety shows – a variety of close-up tricks, and obviously the huge stage illusions like sawing the woman in half, disappearing the elephant, great escapes and disappearances.

“Audience participation was also a big thing.”

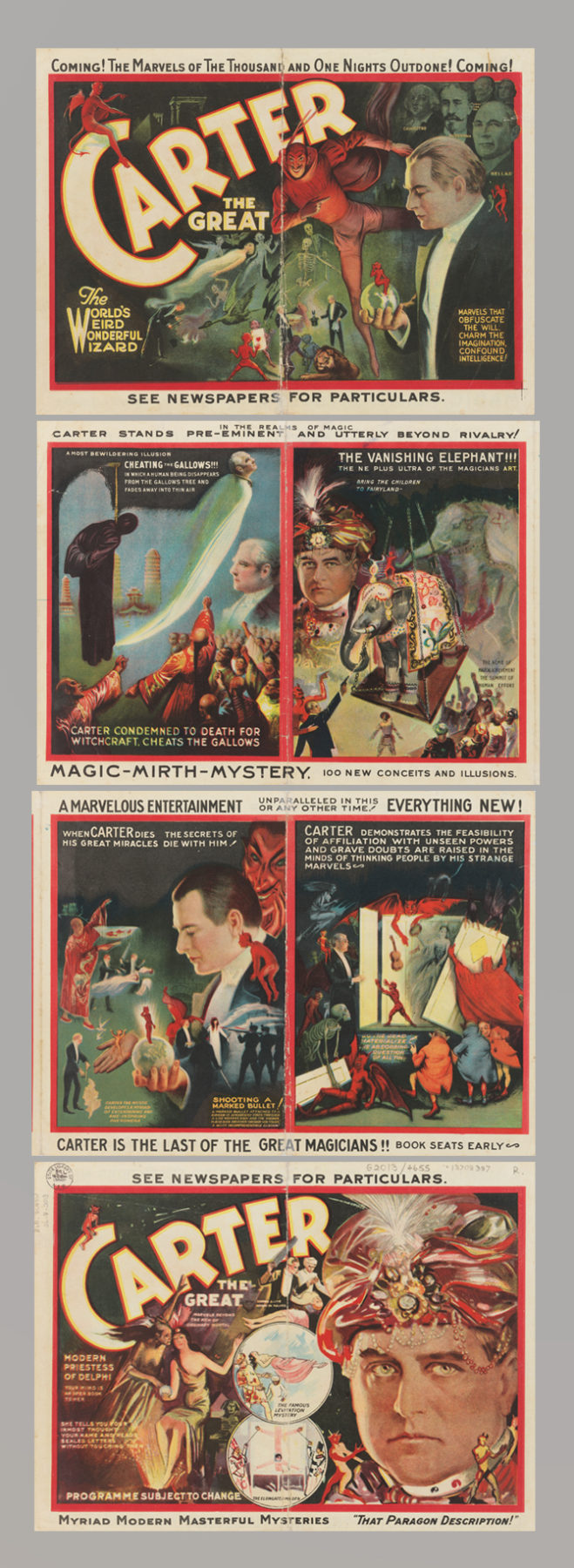

Carter the Great’s greatest illusions

American magician Charles Joseph Carter was known for his extravagant illusions.

When he toured Australia in 1907, he travelled with 28 tonnes of apparatus, everything he needed to pull off these marvels, advertised to ‘obfuscate the will, charm the imagination, confound intelligence’.

One of his most popular spectacles was a trick called ‘Cheating the Gallows’ during which Carter, covered in shroud, would vanish just as he dropped at the end of a hangman’s noose.

“Carter’s show carried a full range of illusions, which grew in size after each consecutive tour,” says Margot Riley, a curator at the State Library of NSW.

Among these were the ‘The Lion’s Bride’ in which a young girl was thrown into a cage containing a live African lion, and in an instant the lion transformed into Carter, dressed in a lion costume, and ‘The Quartered Woman’, following on from ‘The Sawing in Half’ Illusion during which his assistant was ‘severed’ and locked in a complex block with her limbs stretched in all directions.

Then there was ‘The Phantom Bride’.

“This was a simple chair attached to ropes,” explains Margot. “His wife would sit in the chair, and it would be hoisted several feet in the air. Upon his command she would vanish in thin air and the chair would fall to the ground. He originally called this illusion ‘The Magical Divorce’ but apparently his wife didn’t get the joke and made him change the name of the illusion.”

Carter was also famous for ‘The Vanishing Elephant’ – an illusion originally developed by Harry Houdini but adopted and adapted by Carter.

Essentially, an elephant was ushered into the rear of a large cabinet. The cabinet was then closed and the front turned to the audience. On command both the front and back doors were dropped open to reveal the elephant was gone. The audience could only see the back of the stage through a round opening in the cabinet.

– Images courtesy State Library of NSW

Crowd expectations were also remarkably different to those of today. One of the most stark examples of this is the attention span of audiences, says Mark.

“During the Golden Age audiences were so different. For example, Houdini would do an escape that these days would take a minute and a half, maybe two minutes of stage time – he’d take 20 minutes to do it!

“He’d get into a cabinet, be locked up, then they’d put a screen in front of it. The real story is that he would get out of it in about two minutes and then sit down and read a book and wait. Then he’d pop out pretending to be worn out and sweating.

“If we did that nowadays everyone would walk out, get out their phones, and go ‘this is bullsh*t’.”

The next generation

While the history books tell us The Golden Age of Magic came to an end in the 1920s, here in Australia, a new chapter of magic rose in its place.

Inspired by the great international entertainers who had toured here, soon Australia was producing its own celebrity magicians – big names like Magic Murray, Sloggett, The Amazing Mr Rooklyn and the most famous of all, The Great Levante.

After achieving great fame at home, this new generation of magicians also took their shows overseas, forging their own hugely successful international careers.

“During the Golden Age they’d been exposed to those masters, they’d seen those performers”, says Mark.

“They carried that on, even though the Golden Age itself had ended.”

Stay tuned for Part II – The Magic of Magic in Oz, coming soon!