There are few Aussie marsupials as instantly recognisable as the bilby – or more specifically the greater bilby. It’s those ears, of course. But then the bright spark who started the push to replace the pesky introduced European rabbit with the charismatic native bilby as Australia’s Easter chocolate treat of choice may have also had something to do with it.

Despite the proliferation of the confectionary versions, the real bilby is among our most at-risk animals. And it’s the species we’ve chosen to launch our new bi-monthly public fundraising campaign – Australia’s Most Endangered – to highlight our native fauna at the greatest risk of extinction. Funds raised from this campaign will will go towards the national conservation program run by Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC), which is already delivering encouraging results.

AWC is a national operation that’s a global leader in conservation with its science-informed land-management partnership model. Through a large and growing network of sanctuaries located across the continent, AWC aims to protect species and the ecosystems they depend on.

Gracing AWC’s logo is a bilby. Look closely and you might discern that it’s a lesser bilby, the greater bilby’s unfortunate cousin not seen since the 1930s and declared extinct in the 1960s. AWC is determined to prevent the same fate for the greater bilby. The good news is that headway is being made.

Like so many species we write about, bilbies are victims of the same deadly cocktail of challenges that face most of our native creatures – habitat loss, predation by feral invasive species, competition from rabbits for resources, and climate change–driven impacts on vital resources. Bilbies were also hunted by 19th-century rabbiters around Adelaide, where their blue-grey pelts hung alongside those of their feral nemeses.

Significant populations were still being recorded as late as the 1930s around the South Australia–Northern Territory border, but a crash occurred sometime after. Rabbits outcompeted bilbies, the wily European fox decimated them, and feral cats added to the carnage.

The greater bilby is the largest member of the bandicoot family. It shares the same short forelimbs and powerful hind legs as bandicoots. But it has some distinctive differences, such as those large, translucent pink ears and a spectacular long tail with a thick band of black-coloured fur along half its length and a pure white feathery end with a mysterious horny spur. At the time of European settlement, the two species of bilby were found across 70 per cent of the mainland and believed to number in the millions. Now, the lesser bilby is extinct, and the greater bilby is found in just 20 per cent of its former range with less than 10,000 estimated to be remaining in the wild. The greater bilby is now classified as vulnerable nationally, but is locally extinct in NSW.

Conservation efforts have focused on creating feral-free sanctuaries. Among the first of these was AWC’s Yookamurra Wildlife Sanctuary in SA. This 1000ha enclosure was originally established in 1988 by AGS Lifetime of Conservation awardee John Wamsley OAM. This brilliant mathematician and fearless advocate for native animals developed a fencing system that protected smaller animals, such as bilbies and numbats, by keeping out ferals while allowing the passage of larger native species.

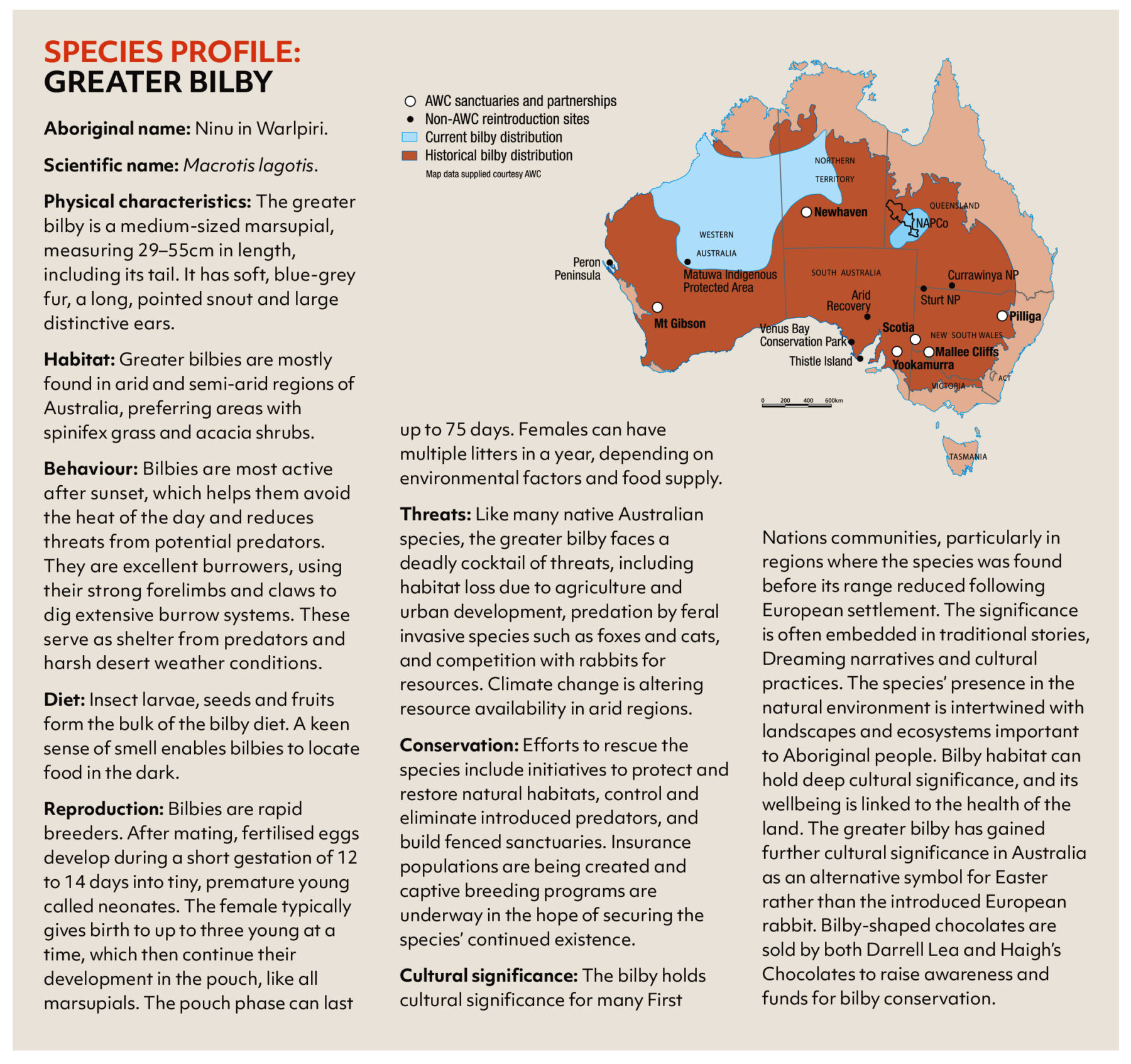

Today, Yookamurra is one of more than 30 sanctuaries and partnership sites where AWC works. John’s revolutionary fence technology has evolved too, allowing the establishment of vast, fenced, predator-free zones across the continent. Currently about 10 per cent of the surviving bilby population is protected within an AWC facility. These sanctuaries – Yookamurra (SA), Scotia (New South Wales), Mt Gibson (Western Australia) and Newhaven (NT), as well as two NSW government partnership projects, in the Pilliga and Mallee Cliffs National Park, all occur where bilbies once thrived but have become locally extinct.

Bilbies are “ecosystem engineers”. “It’s a phrase we use to describe a species that changes the environment it’s in, just by the fact it’s there,” explains Alexandra Ross, AWC Acting Regional Ecologist working at Yookamurra. “The bilby digs holes to live in, but also to find seeds, roots and other foods. These holes collect other things like leaves and debris and bits of seeds. And when rain falls into these holes, it turns them into mulch pots, much like you’d make if you were going to plant something at home.”

Bilbies are known to each move several tonnes of topsoil a year, and they play a critical role in desert ecosystems. The differences between bilby habitat within sanctuary fence lines and beyond them can be dramatic, and those differences explain why it’s vital to reintroduce bilbies to places they occurred naturally. So many other species – both flora and fauna – benefit from their presence.

Maintaining genetic diversity among populations of any species living within enclosures is a grand logistical challenge and animals are carefully selected by AWC staff to create founding populations in new sanctuaries. In 2022, 32 bilby “founders” were introduced to the organisation’s Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary near Alice Springs, NT. A 9450ha portion of this 2615sq.km former cattle property – located on the traditional lands of the Ngalia-Warlpiri/Luritja people – was declared predator-free in 2019, marking the start of one of Australia’s most ambitious rewilding projects. The 32 founders came from Taronga Western Plains Zoo in Dubbo, NSW, and another 34 came from the Queensland government’s sanctuary at Currawinya National Park, which was built with funds raised by the national Save the Bilby Fund. Within a year, evidence of juvenile bilbies was detected in Newhaven, while across all AWC properties the overall estimated bilby population in March 2023 was at least 3315, more than double the 2022 estimate of 1480, and almost triple the 2021 figure of 1230. Bilbies are prolific breeders, and if conditions are right and predators controlled, they can bounce back quickly.

It’s good news for this engaging and iconic creature, and for a whole raft of other embattled species whose survival is inextricably linked to that of the greater bilby. It takes breathtaking courage, ambition and lots of money to tackle Australia’s crashing biodiversity on such a towering scale. But if you can bring just one species back from the brink, it might just bring a whole raft of creatures back with it.