We fan out across the landscape between spiky clumps of spinifex. Heads down and moving as one, we carefully scan the ground in front of us for traces, for clues. We’re all looking for the burrows of a very special animal. I’m here at Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, in Central Australia, to join a diverse team, ranging from Traditional Owners and rangers to citizen scientist school children, assembled to look for tjakura, the great desert skink.

“They [the old people] have been looking after all these tjakura for a long time,” says Cedric Thompson, a Mutitjulu Community Mala Ranger (Anangu rangers who care for Country in Uluru-Kata Tjuta NP). “That’s why it’s for us mob to look after them now.”

Tjakura is a striking desert reptile species that’s of widespread cultural significance for First Nations people. Belonging to the same family as the better known blue-tongue lizards, tjakura is a skink with a solid body. It reaches 45cm in length and has smooth scales coloured orange-red on its upper body, fading to bright yellow on its under-belly – perfect camouflage against the red desert sands. In some places they can also be grey in colour.

Tjakura is the species’ name in the languages of the Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara and Ngaanyatjarra peoples. In other areas, it’s known as mulyamiji, tjalapa, warrana or nampu. In English, the great desert skink is its common name.

Celebrated in art, dance and song, tjakura is an important Tjukurrpa (Creation) animal, and was once a food source, said to taste like fish. But because its numbers have been declining, Traditional Owners are now opting to protect the lizard. Occurring almost exclusively on Aboriginal land, tjakura is endemic to Australia, with a natural distribution across a large part of Western Australia and the Northern Territory, and into the north-western corner of South Australia.

It’s a crepuscular species, meaning it’s most active during dusk and dawn. Termites make up the bulk of its diet, but the lizard is also partial to nibbling on beetles, spiders, centipedes and other invertebrates, as well as parts of plants, including bush tomatoes and paper daisies. Tjakura are least active in the middle of the day when the sun beats down on the desert sand.

To escape the heat, it lives underground in extensive communal burrows. It’s also one of few reptiles worldwide that cares for its young. One burrow is home to a family unit, with up to 10 individuals nestled in – a male, female and their young from multiple breeding seasons.

The small above-ground entrances belie the large, cosy home below. Tjakura burrows are more than 1m deep and up to 10m in diameter, with multiple entrances. On the surface is a communal latrine where all the family deposit their faecal pellets – known as scats. If you want to picture the latrine, imagine that someone has spilt a packet of old chocolate bullets on the desert sand. It’s these scats – also known as kuna in many desert languages – that are helping us to understand more about tjakura. Tjakura have disappeared from many areas, and their population is in decline.

The key threats to the skink are feral animals and unmanaged bushfires. Feral cats are a menace across Australia’s deserts. “When we look at cat kuna, we find a lot of tjakura scales. You can see them; the skin is still orange,” says Dr Rachel Paltridge, an arid-zone ecologist with the Indigenous Desert Alliance, an Indigenous-led organisation strengthening desert ranger teams to keep Country healthy.

“Tjakura is endangered, and we have to monitor them because [there are] a lot of cats and foxes here. When you do a dissection of a cat’s stomach you see all the lizards, skinks and dragons, the whole lot, in a cat’s stomach,” explains Leroy Lester, a senior Anangu Traditional Owner and Parks Australia Anangu Engagement Officer.

Unmanaged bushfires also pose a major threat to tjakura. In the past, Traditional Owners carried out regular burns with fine-scale fire mosaics – they burnt small patches of the landscape and left other patches unburnt where animals could seek refuge. But since European colonisation, there are more hot, unmanaged fires – sometimes started by lightning – that sweep across large swathes of the landscape and raze everything in their path.

When bushfires and ferals combine, tjakura fight a losing battle. Unmanaged bushfires remove the protective cover of plants such as spinifex from around tjakura burrows. Although skinks usually survive the fire, they become easy prey for feral cats and foxes.

Vital Indigenous knowledge

Tjakura are now confined to a small number of locations. The species is nationally classified as vulnerable to extinction. “This means,” as the skink’s National Recovery Plan explains, “that it is at risk of going extinct in the wild (in the next 100 years) if nothing is done to manage threats.”

This is where Indigenous rangers are vital. Yes, tjakura are threatened. But the species is also thriving where Indigenous rangers are looking after Country – controlling feral cats and re-establishing traditional fire regimes.

But part of the puzzle is still missing. We don’t have a solid understanding of tjakura numbers, and whether the population is increasing or declining.

And that’s why I’m here, with a wonderfully diverse team made up of Anangu Traditional Owners, Mutitjulu Community Mala Rangers, Indigenous rangers from nearby areas, scientists, Parks Australia Rangers, and school kids from near and far.

We’re camping in the heart of World Heritage-listed Uluru-Kata Tjuta NP, and each morning we’ll be up before sunrise. It’s already warm at 6.30 and the mercury will rise daily to 41°C for the rest of the week. To say the location is stunning is an understatement. We’re flanked by two of Australia’s most iconic sites: to the east lies Uluru, the sandstone monolith in all its glory, and to the west is Kata Tjuta, with its domes glowing in the morning sun.

About 30 of us are camping out, and on the first morning, as everyone begins to stir, heads emerge from tents and tarps pitched under a small patch of mulga trees.

We make cups of tea and coffee and load up on breakfast before we embark on five long days of surveys. From dawn to dusk, we’ll work together to look for tjakura burrows and their latrines, recording important scientific information. We want to know if there are more or fewer active burrows, compared with what the surveys found in 2023.

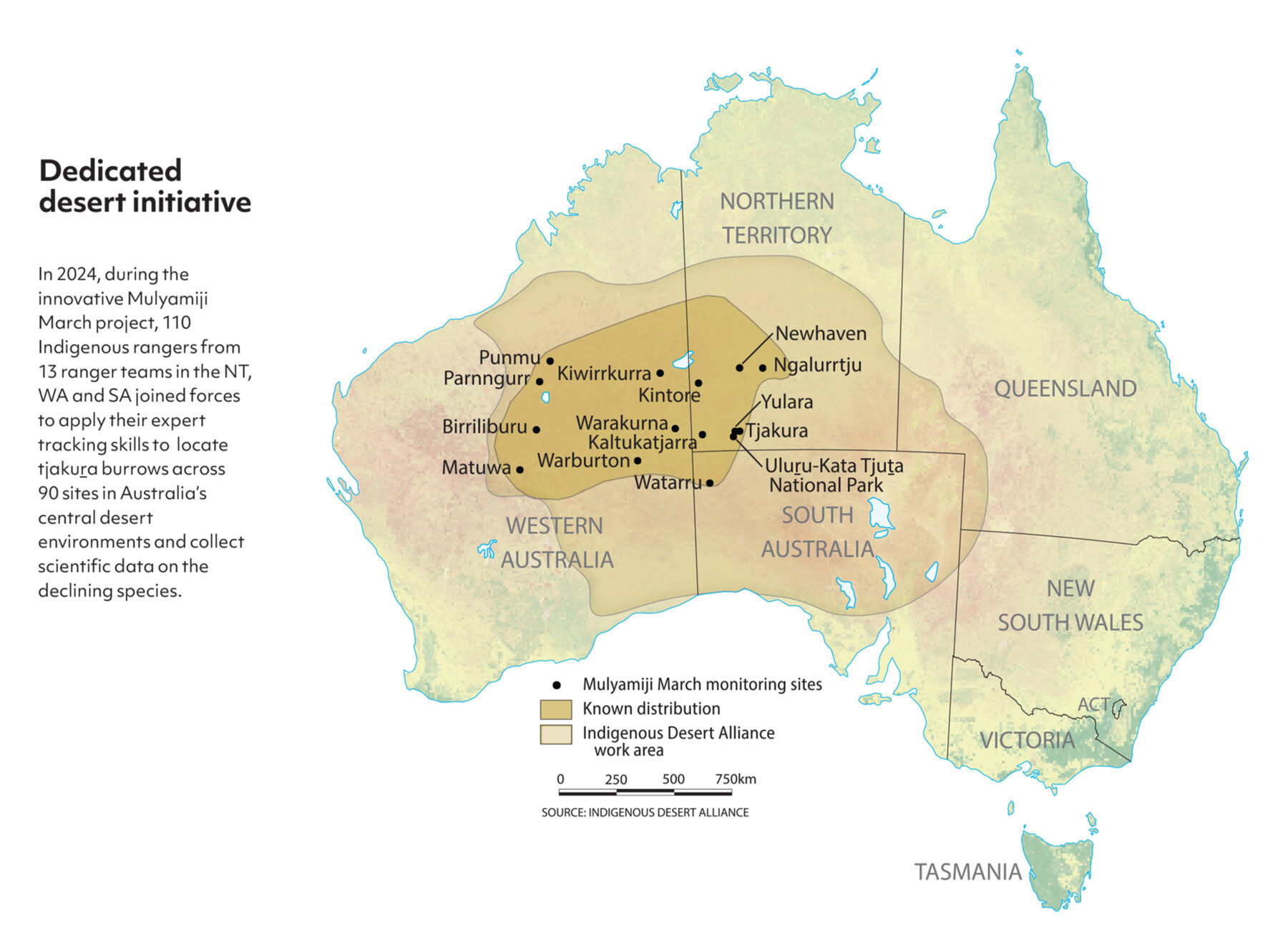

This extraordinary monitoring program is called Mulyamiji March. Mulyamiji is the Martu name for the skink. And March is the designated month for ranger groups to march across the desert doing their surveys. It’s the largest collaborative threatened-species monitoring program in Australia’s deserts. The ranger groups are spread across 500,000sq.km – seven times the size of Tasmania.

The driving force behind Mulyamiji March is Rachel Paltridge, who is funded by the National Environmental Science Program’s Resilient Landscapes Hub (known as the hub).

“The exciting thing about this project is that we’re developing a scientifically robust monitoring method that’s based on expert tracking skills,” Rachel says. “With so many rangers involved, all using a consistent method to collect the same information from nearly 100 sites across the desert, we can pool the data to create a really powerful dataset to monitor trends in the national population.”

Understanding the size of the population and how it’s trending over the next 10 years is also a key strategy under the ‘Indigenous Desert Alliance (2022), Looking after Tjakura, Tjalapa, Mulyamiji, Warrarna, Nampu. A National Recovery Plan for the Great Desert Skink (Liopholis kintorei)’. This is the first Indigenous-led recovery plan in Australia. The Australian government has listed tjakura as a priority species under the 2022–2032 Threatened Species Action Plan, and is supporting ongoing monitoring and recovery efforts.

The Resilient Landscapes Hub provides scientific advice to support work under the recovery plan. For example, it created standardised monitoring methods and a power analysis so information can be accurately compared about tjakura across its range. The first Mulyamiji March was launched here in 2023, involving 13 Indigenous ranger teams from the NT, WA and SA. Together with Traditional Owners, scientists, and land managers, they surveyed 90 sites and found 541 active tjakura burrows.

Reading the signs

So here we are in 2024 and the second year of Mulyamiji March surveys is underway at Uluru-Kata Tjuta NP, a stronghold for the species. After waking up in the desert, we join a convoy of four-wheel-drive troopies to the first survey site, each of which is a 10ha rectangle. We split into a group of men and a group of women, walking up and down the monitoring sites. Tracking skills are needed to find the burrows, and the Indigenous rangers’ expertise is key to the success of this project.

“It’s amazing how much detail people can read in the tracks: the size of animals, what they are doing, which predators are hunting around their burrows,” Rachel says.

And how do you know who is living underground when you find a burrow? The clue is in the poo. If a latrine has fresh, dark-brown scats, it indicates there are tjakura in the burrow below and the burrow is considered active. The size of the scats also reveals who is below – large scats suggest adults, for example. The rangers enter all of this information, plus photos and other details, into a tablet. This data will be used to monitor how the tjakura population is changing year to year.

Mulyamiji March is not just about science. It’s also about culture. To celebrate the monitoring program, artists from Walkatjara Art, an Anangu-owned not-for-profit art centre, have made large sculptures and several paintings of tjakura. Other ranger teams visit sacred Creation sites for tjakura to conduct increase ceremonies for this culturally significant species.

The project is also about sharing knowledge. The Tjuwanpa Women Rangers from nearby Hermannsburg (Ntaria) are joining the Mutitjulu Community Mala Rangers this week to learn how to do their own lizard surveys. They are led by senior ranger Sonya Braybon.

“The Uluru and Mala rangers invited us,” Sonya says. “We feel really happy to join them and do some surveys on their sites here. We’ve learnt a lot. It was great to see a live desert skink, the tjakura, and nice to meet the scientist people as well.”

Mulyamiji March is also about passing knowledge on to the next generation. Troops of school kids and recent school-leavers join us for surveys during the week: some students are from the local Nyangatjatjara College, outside Yulara; other students drive all the way from Warakurna in WA, a 330km journey.

At first the kids laugh at the idea of measuring kuna, but in no time they’re scouring the spinifex for tjakura burrows and latrines and helping enter data into the tablet.

Importantly, Mulyamiji March is also about having fun. In 2024, there are several competitions between the participating ranger groups. Which group will cover the largest number of survey sites? Which group has the best school participation? Who can capture the best photograph of a tjakura? The stakes are high: the legendary television reporter Barranbinya man Tony Armstrong will present the awards, including the coveted Most Burrows trophy.

The team effort continues

It’s a full week of monitoring tjakura at Uluru-Kata Tjuta. Each night we drive back to the camp, sharing food and stories, and getting ready for the next day of surveys. In total, we cover 34 sites in the 41°C heat.

Then, with the Mulyamiji March surveys done at Uluru, the rangers set to work, doing the cat-control activities and mosaic burning that give these skinks a fighting chance. Rachel hits the road, driving to the next monitoring sites, supporting the next team of Indigenous rangers and expert trackers as they march across the desert, searching for tjakuraa.

With this team effort, along with First Nations knowledge and western science, we’re hoping these skinks will continue to appear at their burrow entrances, warming themselves in the early morning sun for generations to come.

Kate Cranney is the Communications Manager for the National Environmental Science Program’s Resilient Landscapes Hub, which partners with the Indigenous Desert Alliance for Mulyamiji March. Through the hub, researchers ensure that the science behind the survey is robust, so that the data collected can accurately indicate if the tjakura population is increasing or decreasing across the country.

Keeping the desert connected

Brought to you by Indigenous Desert Alliance

The Indigenous Desert Alliance (IDA) is an Indigenous-led organisation strengthening desert ranger teams who work together at landscape-scale to keep Country healthy. Together with its members, including 65 Indigenous ranger teams, the IDA facilitates the largest Indigenous-led and culturally connected conservation network on Earth.

The IDA works to enable a strong and united voice for Indigenous desert rangers, to support strong and sustainable ranger teams, and to ensure the future health of Australia’s precious living deserts.

Learn more about how you can support the IDA’s vital work.

Looking After Tjakuṟa

Rangers across the Australian desert have joined forces to protect the iconic great desert skink – or Tjakuṟa – also known by different Aboriginal language groups as Tjalapa, Mulyamiji, Warrarna, and Nampu.

The great desert skink is a species of cultural significance for Indigenous people, both as an important Tjukurrpa (Dreaming) species and, historically, a favoured food resource. It occurs almost exclusively on Aboriginal land.

Threatened by the combined impacts of unmanaged wildfire and feral cat predation, these iconic lizards have disappeared from many sites where they were formerly known. But they continue to thrive in areas where Indigenous Rangers conduct traditional burning and/or cat management.

The IDA is coordinating the implementation of priority actions in the Great Desert Skink Recovery Plan with support from the Australian Government’s Saving Native Species Program and the National Environmental Science Program’s Resilient Landscapes Hub.

Ranger Teams are supported to record cultural knowledge, conduct surveys, establish monitoring programs, and manage fire and cats around great desert skink sites. A collaborative, simultaneous, tri-state monitoring event called ‘Mulyamiji March’ is conducted annually.